Listen My Children… The Untold Story of Not Paul Revere

Photo: Sutori.com

700 British soldiers stationed in Boston mobilized under cover of darkness. They overpowered a small group of patriots in the town of Lexington, Massachusetts, they marched toward Concord, where they planned to confiscate the local militia's stash of ammunition. But things didn't go that way. When they arrived they found nearly 400 men waiting for them. Someone had warned the rebels that the British were coming.

This warning, as most Americans will tell you, came from Paul Revere, the brave Boston patriot who charged through the night on horseback to spread the alarm. Thanks to the midnight ride, the stage was set for the birth of a new nation.

This narrative is central to America’s founding myth. It also isn’t entirely true.

Friday marks the 250th anniversary of Revere’s ride, which began late on the night of April 18, 1775. But the story many Americans heard growing up dates to 1861, when the Atlantic Monthly It opens with the famous couplet: “Listen, my children, and you shall hear / Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere.”

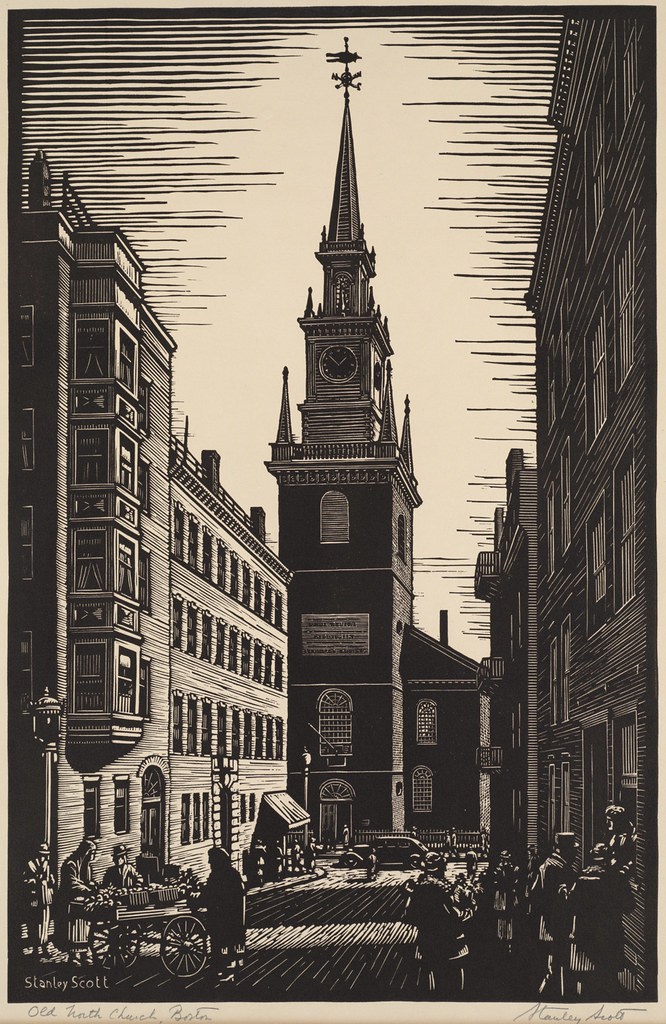

The story many of us know is really from the famous poem published in 1861 by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. In Longfellow’s version, Revere directs a fellow rebel to signal information about the British soldiers’ movements by hanging lanterns from Boston’s Old North Church: “one if by land, and two if by sea.” After rowing across the Charles River, Revere waits for the signal. When two lamps appear in the belfry tower, he “springs to the saddle” and rides “to every Middlesex village and farm”—finally arriving in Concord by 2 a.m.

In reality, Revere was one of many riders who raised the alarm that night. Some of their names have been lost to history, but at least two others feature prominently in historical accounts: William Dawes, who set out from Boston an hour before Revere, and Samuel Prescott, who arrived in Concord alone around 1:30 a.m.

In reality, Revere had never made it to Concord-he had been captured by the British.

So who were these other riders - and how did they figure in to the colonist's plans? Meet patriot leader Joseph Warren. Warren was the man who sent for Revere, and his back-up. Before Revere ever arrived, Warren had already dispatched another rider to warn the townsfolk—a Mr. William Dawes.

Revere, was known as a fierce revolutionary, so Warren figured that Dawes might be able to bypass the checkpoint without raising suspicion, due to the fact his business often took him through the area. At the same time, Warren directed Revere to deliver an identical warning to Lexington via a different route. That way, even if one messenger were apprehended, the other would still have a chance.

What about the famous lanterns?

Photo: Stanly Scott c.1939 Archives.gov

Turns out that was Revere's idea - and it wasn't intended for him at all. He set that plan up about a week earlier, figuring they would act as a back-up in case he, or any other messenger, was captured. Fellow patriots in Charlestown indeed saw the lantern signals and dispatched additional messengers.

The poem isn't all wrong. Revere later wrote that he was equipped with “a very good horse,” and he set off for Lexington around 11 p.m. Along the way, he knocked on doors and spread the alarm in “almost every house.”

As Revere roused the countryside, Dawes was also making his way toward Lexington. But history does not record Dawes as being very effective. Very few people from the towns and areas Dawes rode through then made it to Lexington and Concord the next morning. He may not have alerted hardly anyone.

Around midnight, Revere arrived in Lexington, and Dawes, who had taken the longer route, joined him about half an hour later. When the two men set out for Concord together, they by chance encountered Prescott, a 23-year-old doctor who was in Lexington at the time. Prescott lived in Concord, knew the territory, and offered to ride with the pair.

But as the three men rode into the night, they ran into British patrols. Legend has it that Dawes escaped the British by riding into the yard of a house and shouting, “I’ve got two of them—surround them!” as if he were addressing a large group of fellow rebels. While the ruse worked in scaring off his pursuers, he also fell off his horse. Prescott rode his horse over a stone wall and escaped. Navigating the terrain he knew well, he flew past his own house toward the center of Concord.

Revere never made it to Concord. He was captured by the British and questioned. They took his horse and finally let him go. After that, Revere decided to walk back to Lexington.

Why the Poem?

The midnight ride didn't come to define Revere's legacy until Longfellow decided to single him out in his poem. But why him? One possibility: Revere has been doing this regularly. The midnight ride is not his first ride. Unlike Dawes and Prescott, Revere was intimately involved in the revolutionary cause, and he wrote detailed accounts of his experiences.

After all, Revere was the man behind the lantern signals, even if the details don’t quite align with Longfellow’s narrative. He also may have spread the warning more efficiently.

While never proven, a common suggestion is that Longfellow spotlighted Revere because Dawes’ name doesn’t work as well with the rhyme scheme.

Not Forgotten

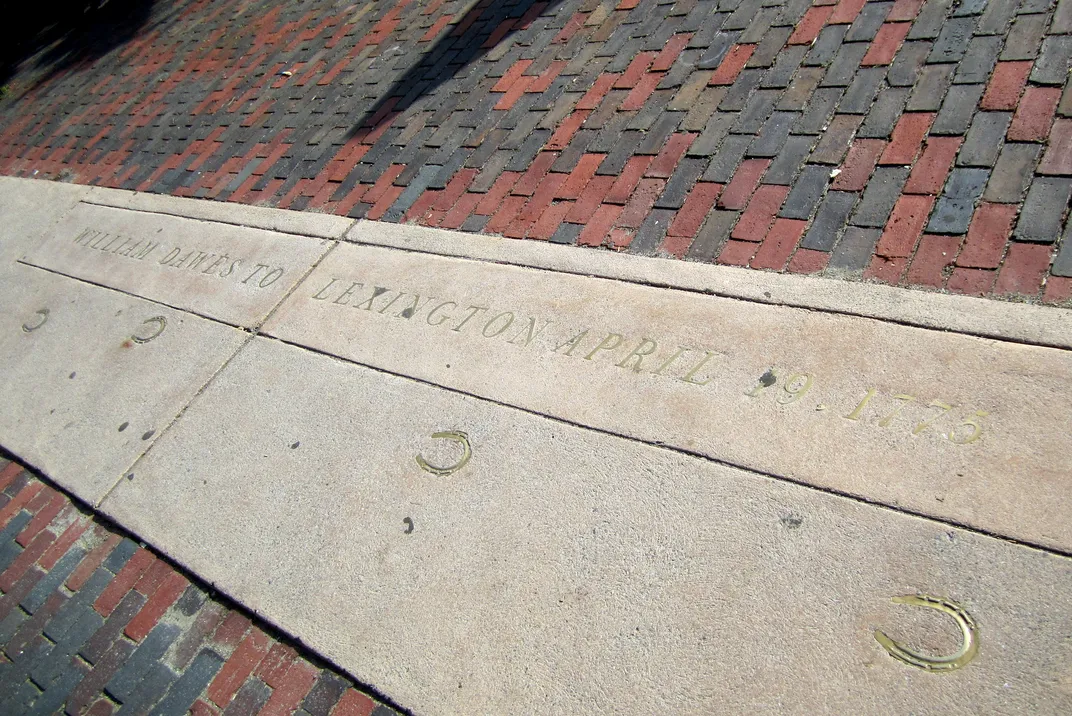

Today, Dawes’ descendants are trying to boost their ancestor’s reputation. The Paul Revere House describes his role, but don't try visiting the William Dawes House. There isn't one. In nearby Cambridge, a traffic circle called Dawes Island features a trail of bronze hoof prints commemorating the ride.

Dawes Island is a traffic circle in Cambridge, Massachusetts, commemorating Dawes' ride. Wally Gobetz via Flickr under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Barb Moberg, president of The Descendants of William Dawes, Who Rode, Association said "I just think Paul Revere had more marketing.”

The association hopes to correct that imbalance. Its members have been trying to establish some sort of memorial to honor Dawes at Forest Hills Cemetery, where his body was moved to an unmarked grave in the 19th century. Prescott, on the other hand, is thought to have died in a British prison, and has no known decedents trying to promote his legacy.

The Paul Revere House tries to present a balanced take on the midnight ride, which it examines in a permanent exhibition. It also tries to present a more nuanced view of Revere, exploring his life beyond the midnight ride—including his “deeply unspectacular” military service and his later legacy as the first American to successfully roll copper into sheets.

This article can be found at Smithsonianmag.com